Barrels of Pesticide Haunt California’s Coast

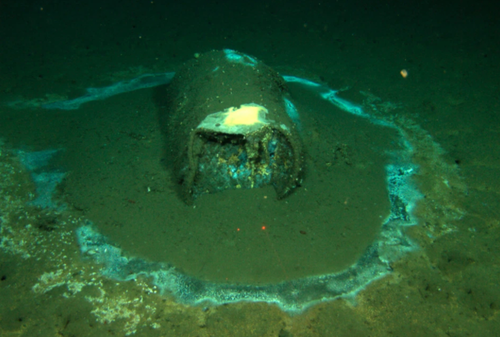

Barrel of DDT on the ocean floor.

February 2, 2022

Twelve miles off the coast of Los Angeles, a monster lurked in the deep. UC Santa Barbara professor, David Valentine, was the first to hear its rumblings in 2011. After deploying a deep-sea device to snap images of the ocean floor, Valentine and his peers were alarmed, and it wasn’t difficult to see why; corroding barrels of toxic waste littered the depths. Sediment samples of the affected area identified the culprit: dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, or DDT, a pesticide banned in the early 70s for its adverse environmental effects.

From 1947 to 1972, Montrose Chemical Corporation of California was the number one manufacturer of DDT in the country, most notably, the pesticide was used to fend off malaria and typhus in the Pacific theater of World War II. One small application of the substance could protect a soldier for months. After the war’s end, the demand for DDT remained high, now popular in a new market as the population ballooned. Its success in insect control would see it used as an agricultural pesticide. Throughout the 1940s, 50s, and 60s because of skyrocketing production, Montrose had an excess chemical waste from the synthetization process. The question of what to do with the waste arose. And, even with their expansive board of directors and their chemists creating the product, the best solution, it seemed, was to pack the waste into metal barrels and dump those barrels into the Pacific. Their actions weren’t out of naivety to the effects of dissolved oxygen and pH on these metal barrels’ corrosion processes, but out of laziness and a blatant disregard for the environment.

1972 saw Congress enact the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, which ensured that the government would (finally) regulate waste dumping that negatively affected human and marine health. In the same year, DDT was banned in the US, its declining usefulness against pesticide-resistant insects, and the striking realization that its waste was dangerous, being the two main factors for termination. In 1990, the EPA classed the known DDT dumping grounds as a superfund site, a polluted location requiring long-term cleanup. Prior to Dr. Valentine’s discovery, an estimated 100 million tons of DDT was present in the sea floor sediments. From 2011-2021, researchers from UC Santa Barbara and UC San Diego’s Scripps Institute of Oceanography, were able to survey 36,000 miles of seabed not in the EPA’s recordings, and found far more than they bargained for. In those 35,000 miles, more than 25,000 barrels of DDT waste had been found.

DDT’s malevolent presence in the water wasn’t unknown to scientists, but prior to the unearthing of the additional barrels, high amounts of the substance in the bodies of marine life was puzzling. Large swaths of the population of white croaker, a bottom feeding fish, developed tumors likely after ingesting smaller organisms with high concentrations of DDT in their systems. In 1969, shipments of jack mackerel from southern California were recalled because DDT levels were as high as 10 parts per million in each fish (2x what was normal). DDT takes years to break down, and bioaccumulation in marine organisms occurs, endangering the entire food chain. Phytoplankton are exposed to DDT in high amounts proportional to their small size, they are eaten by zooplankton, which then consume the DDT by default. Zooplankton are abundantly consumed by fish and whales, which increases the amount of DDT in their systems, and so on. Fish were not the only victims of the toxic waste. Sea lions with more than 1,000 ppm of DDT in their blubber gave birth to premature pups. The eggshells of seabirds were so thin that the chicks would die. Despite the agony suffered by sea creatures for decades, news of the new barrels never hit the front-page headlines because DDT is not explicitly harmful to humans (Only in incredibly large doses). Beachgoers were free to surf and swim, just don’t eat any white croaker you catch!

Dr. Valentine and the team do not have a set plan to allay further risks posed by the barrels. The best they can do for now is to study their contents and strategize how to ensure the welfare of human and marine life. A normal person cannot dive 3,000ft into the ocean and retrieve leaking chemical waste barrels, but they can take steps to stop chemical runoff from going into local water sources. Use the least toxic products possible, read labels and dispose of waste properly DON’T LITTER. If there is to be a development in your area, rally against it. Seriously. Developments create an enormous amount of runoff that contaminate water. Stay informed on environmental issues! You never know when the EPA could release a statement saying that all the soil in Baltimore County is contaminated with super arsenic anthrax ricin.