Sista Grrrl: The Feminist Mother of Afro-punk

Before there was Afro-punk, there was Sista Grrrl. Ever since the beginning of punk, the voices of marginalized groups were drowned out by a white male-dominated demographic. Discrediting their vital role within the punk community, people of color and female creatives were forced into the underground of the punk world while white males had far more exposure. Sexism and a lack of intersectionality was evident within the community, leaving people of marginalized groups to feel unappreciated and unrepresented. Many felt deprived of a safe space to talk about their frustrations towards societal issues such as discrimination, despite punk’s main component being to uplift the voices of the unheard.

The shared frustration of women during the early 90s led to the development of Riot Grrrl, one of the most influential feminist movements of all time. Within the movement, homemade publications of art and writing known as “zines” were collectively shared throughout cities. Zines acted as a gateway for women to share and discuss political or taboo issues among them such as eating disorders, rape, and domestic abuse. Bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Sleater-Kinney were the most influential parts of the movement. Their abrasive and confrontational lyrics expressed the pent-up emotions many women shared and related to while also empowering young women to challenge the patriarchy. The electric guitar became a symbol of self-expression and liberation as women shredded riffs in raw, avant-garde styles that were considered untraditional and non-conforming.

Although Riot Grrl was made to uplift the voices of women, it suffered from the same issue that the original punk scene had: lack of intersectionality. Riot Grrrl gave voice to an underrepresented demographic within the punk community, however, the movement was soon oversaturated with middle-class white women. In a 2015 VICE article, Gabby Bess, the writer, mentions that “the typical Riot Grrrl as outlined in an infamous 1992 Newsweek article that defined the movement for the mainstream, was ‘young, white, suburban, and middle class.'” In NYU’s Riot Grrrl collection, consisting of various archived remnants of the movement, only one zine was written by a black woman. In 2013, Laina Dawes, a black woman who wrote about her experience as a teenager within the Riot Grrl era, said, “these women activists created a movement that was only relatable for them and there was no thought given to the inclusion of women of color. We were expected to be glad that they were fighting for us because we shared the same lady parts. That was not —and still is not—the case.” The white-majority that led Riot Grrl muffled the voices of women of color, and as a result, many felt as though they were outcasts within the community.

Majority of the issues addressed within Riot Grrrl were expressed from a white, close-minded perspective. Many zines, bands, and even the Riot Grrrl Manifesto itself acknowledged the issues of racism and white privilege in society, yet the majority of POC voices were ignored, denying them a safe-space to express their emotions and frustrations. Sure, Riot Grrrl uplifted the voices of women, but the majority of those women were born with advantages within society that women of color do not have. The movement catered towards young women who were already privileged, and many women of color recognized that during its peak. These women were artists, and like all artists, they deserved a space that validated their expression of raw, unrefined emotion as equally as the white majority. As Riot Grrrl continued to disregard women of color and their contributions to the scene, many of them left. Despite their departure, many of the former Riot Grrrls were tired of penting up their emotions. With no other space to express themselves, they interacted with each other. They shared their issues and experiences, and the former members each saw each other within themselves. Eventually, these interactions became the foundation of a new community.

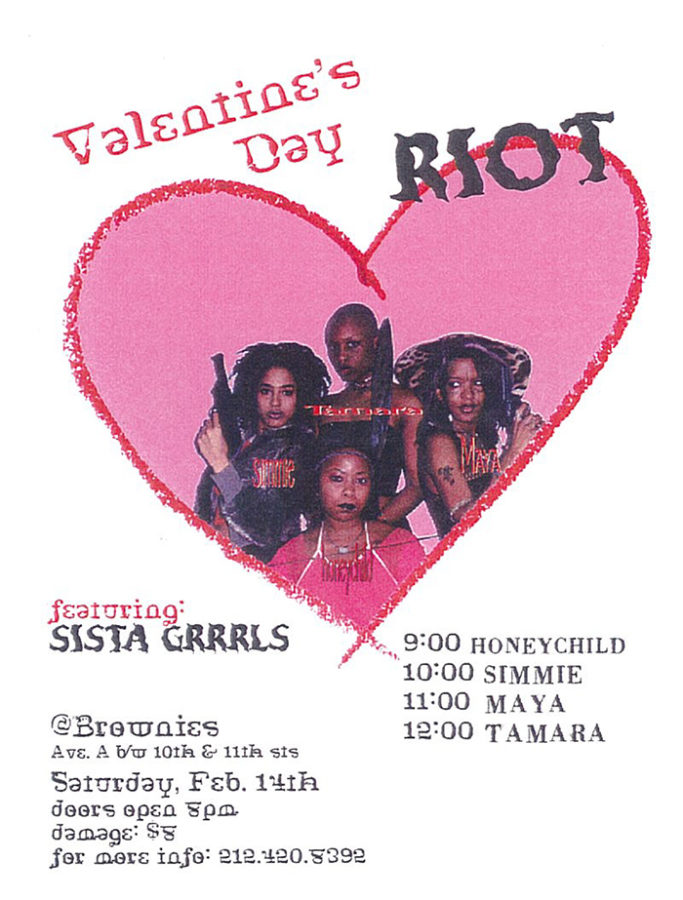

In the late 90s, Tamar Kali-Brown, Simi Stone, Honeychild Coleman, and Maya Sokora met up and created the Sista Grrrl Riots in response to the Riot Grrrl movement. Unlike the previous movement, the Sista Grrrl Riots were made by black women for black women. Many former Riot Grrrls attended sold-out shows at popular clubs such as Brownies and CBGB. The voices of the ignored were reverberated by the Sista Grrrls. Distorted guitars, bombastic drums, and the voices of female punks were amplified through the shows. This counterculture liberated black female punks from restricting their self-expression. The Sista Grrrl Riots created a community that challenged the notion that punk is reserved for those who are white. As Riot Grrrls, these women were rarely heard, but as Sista Grrrls, their sound and statement spilled out of venues and changed punk forever.

Although Sista Grrrl was short-lasting and ended abruptly, it built the foundation of contemporary Afro-punk. Despite popular belief, Afro-punk is not a music genre. Afro-punk bands exist, but the term itself refers to the participation of black people in alternative scenes. The term was founded in 2003 when James Spooner released a documentary titled “Afro-punk: The Rock.” Within the documentary, Spooner explored the roles of African-Americans in the predominantly white punk scene. Tamar Kali-Brown made a special appearance in the film. As she prepared to venture outside, she described her experience of growing up as a black woman as: “being caught in a system that you can’t identify with, that you don’t support, and, like, just being contrary…. That’s the true energy of what punk is.” Tamar Kali-Brown may be an underground artist, but she is undoubtedly the poster-child of afropunk.

Despite Sista Grrrls discontinuation, all four of the original Sista Grrrls continue to contribute to the black alternative scene. To this day, they participate in bands and write songs that share aspects of the old Sista Grrrl sound. Modern black-fronted bands such as Skinny Girl Diet and Big Joanie are influenced heavily by the old scene.

Sista Grrrl is a movement that deserves more recognition for its rich contribution to society today. Without the Sista Grrrl Riots, which amplified the voices of unheard black women, Afro-punk would not be what it is today.

Amanda Amadi-Emina • Jan 18, 2023 at 10:46 am

I can see why this is still trending, interesting topic, strong voice, 10s across the board!!