What Does AI Mean for Us?

January 13, 2023

In Ghost in the Machine, one of the songs on her highly-anticipated new album, singer-songwriter SZA makes a proclamation fit for a headline: “Robot got future, I don’t.” Reading sensationalized news stories about artificial intelligence performing unbelievable tasks, it’s easy to feel the same. As AI bots that write, draw, and even code flood the Internet, a morbid cultural obsession grows: how far will this go?

The Carver Center community is both curious and anxious about these new developments in artificial intelligence. “After continually hearing about ChatGPT online, I decided I would make myself an account,” Emerson Lomicky, ‘23 (he/him) reports. “From finding senior quotes to writing full-on Unity code scripts, I was really impressed by the AI.” The AI engine he references, ChatGPT, has captured much of the growing technology craze. It functions as a simple chatbot; the user inputs prompts for the bot to answer. An Atlantic article titled, The End of High-School English, even argues that this particular chatbot will force English teachers everywhere to reinvent their curriculum.

As an IT student applying to colleges as a computer science major, Emerson also worries about job security: “I’m excited to see where this technology takes us, but also a little apprehensive because of the possibility of certain jobs being automated in the future.” Of course, modernization has been expanding for decades now, but advanced artificial intelligence frightens real human workers trying to make a living — especially young people preparing to enter the workforce.

Carver’s new computer science teacher, Mr. Pritchard (he/him) wants his students to embrace the change. “Students need to understand how AI is modeled so they can understand potential biases and also look at potential careers [where] AI has a large component.” If you can’t beat the omnipresent threat of robot evolution, join it.

But for now, these systems are far from perfect. Popular coding help forum, Stack OverFlow has banned answering questions with ChatGPT-generated responses, citing that “while the answers which ChatGPT produces have a high rate of being incorrect, they typically look like they might be good and the answers are very easy to produce.” ChatGPT’s literary skills are no better, often producing flat and uninspired writing samples. It’s not the fault of the AI or its developers — robots simply can never be human nor will they ever be able to access human emotions.

When I asked Rachel Glen, ‘23 (she/they) about the potential effects AI will have on artists, she sent me no less than 7 videos. It seems the online art community has banded together against a common enemy. As art YouTuber mewTripled explains, “Artists are already undervalued enough, sadly, and bringing in AI art will honestly, probably, contribute to further that to some degree.” Many artists on the Internet supplement their income with commissions — customers buying freelance pieces from artists. To mewTripled, the advancement of AI means “They’re probably going to be less likely to reach out to an artist and commission them for work,” which narrows artists’ means of supporting themselves. In an attempt to circumvent this, Rachel and other Carver Center artists have been raising awareness on social media about the importance of commissioning real artists.

To generate realistic art pieces, AI art applications must be shown millions of artworks — almost always without compensation or permission from the real human artists behind every stroke or splatter. So many of the AI images circulating online incorporate artists’ distinctive styles, frustrating creators and making it difficult to invoke any legal action against AI developers.

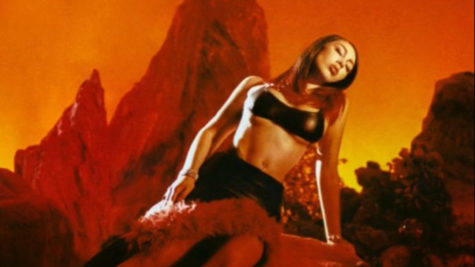

The growth of artificial intelligence also spotlights its biases. Melissa Heikkilä of the MIT Technology Review describes how viral AI avatar generator app, Lensa, oversexualized her compared to her white and male colleagues: “Because the Internet is overflowing with images of naked or barely dressed women, and pictures reflecting sexist, racist stereotypes, the data set is also skewed toward these kinds of images.” While her male co-workers were transformed into “astronauts, fierce warriors, and cool cover photos for electronic music albums,” the AI turned Heikkilä’s photos into avatars wearing “extremely skimpy clothes and overtly sexualized poses.” As an Asian woman, Heikkilä is accustomed to fetishization and misogyny, but seeing it encoded into the technology of tomorrow is especially troubling.

Before artificial intelligence can be fully integrated into our lives, we need to work to eliminate the infinite biases rooted in all predictive software. And while the solution to this problem — including more diverse data sets in machine learning — seems simple enough, it requires us humans to confront our preconceptions while analyzing how our online activity helps perpetuate stereotypes.

In 2019, the Harvard Business Review proposed some ways to minimize bias in artificial decision-making: following new data research closely, using external tools to audit data analysis, and most importantly, complementing AI engines with teams of human decision-makers. People, with all their flaws, are better equipped to recognize prejudices in data than robots designed to mine through numbers and letters. The answer to many problems with artificial intelligence is agonizingly uncomplicated: human intelligence and creativity.

Its weaknesses ensure that artificial intelligence won’t snowball into the end of human expression as we know it, but it will remain an obstacle until it’s reconfigured to work for us, not against us.